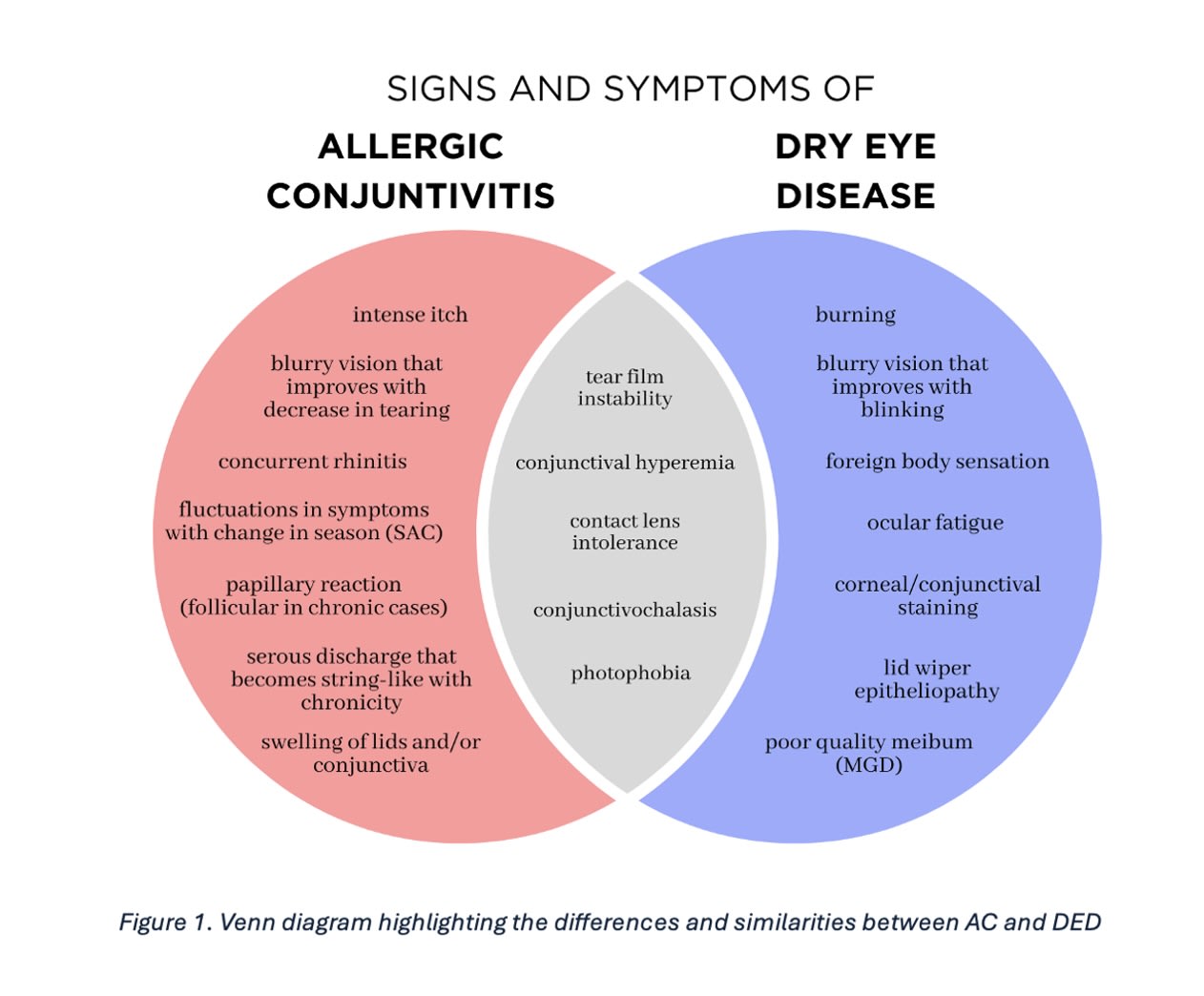

Distinguishing dry eye disease (DED) from ocular allergy can be a challenge. For one, ocular allergy and dry eye disease (DED) are the most common ocular surface disorders resulting in a red-eye response. For another, burning and itching remain commonly reported symptoms for each condition. What muddies the diagnostic waters even further is that both DED and ocular allergy often co-exist, with each creating or worsening the symptoms of the other.

Given this data, the fact that this is Optometric Management’s annual Dry Eye issue and summer allergens are in full swing, here, we discuss how to arrive at an accurate diagnosis. Additionally, we talk about the current ocular allergy interventions available. (For DED interventions, see “Prescribing for Dry Eye Disease,” also in this issue.)

Arriving at an Accurate Diagnosis

The 3 ways to achieve a definitive diagnosis, so that the patient receives the most appropriate intervention(s), are to:

1. Obtain a thorough case history. While it is important to recognize the commonalities among allergic conjunctivitis and DED, it is equally important for the optometrist to remember the other causes of ocular discomfort and redness. Specifically, this clinical sign (redness) and symptom (discomfort), respectively, can also be found in infections, such as viral or bacterial conjunctivitis.

To rule out infection, we recommend the OD ask the patient whether their symptoms first began in one eye and spread to the other, whether they experienced a recent systemic illness diagnosis (eg, autoimmune disease), a recent cold or flu, or whether they were recently in close contact with other individuals suffering from ocular discomfort and redness. Incidentally, viral and bacterial conjunctivitis present with more severe symptoms.

The optometrist must also consider whether the patient is a contact lens wearer or exposed to other material(s) causing chronic friction to their ocular surface, in which case giant papillary conjunctivitis and superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis should be ruled-out.1 Further, the OD should inquire with the patient about any past refractive surgeries, systemic medication use, and any OTC ocular treatments that may contain preservatives. This is because we know all too well that these items are associated with causing DED.

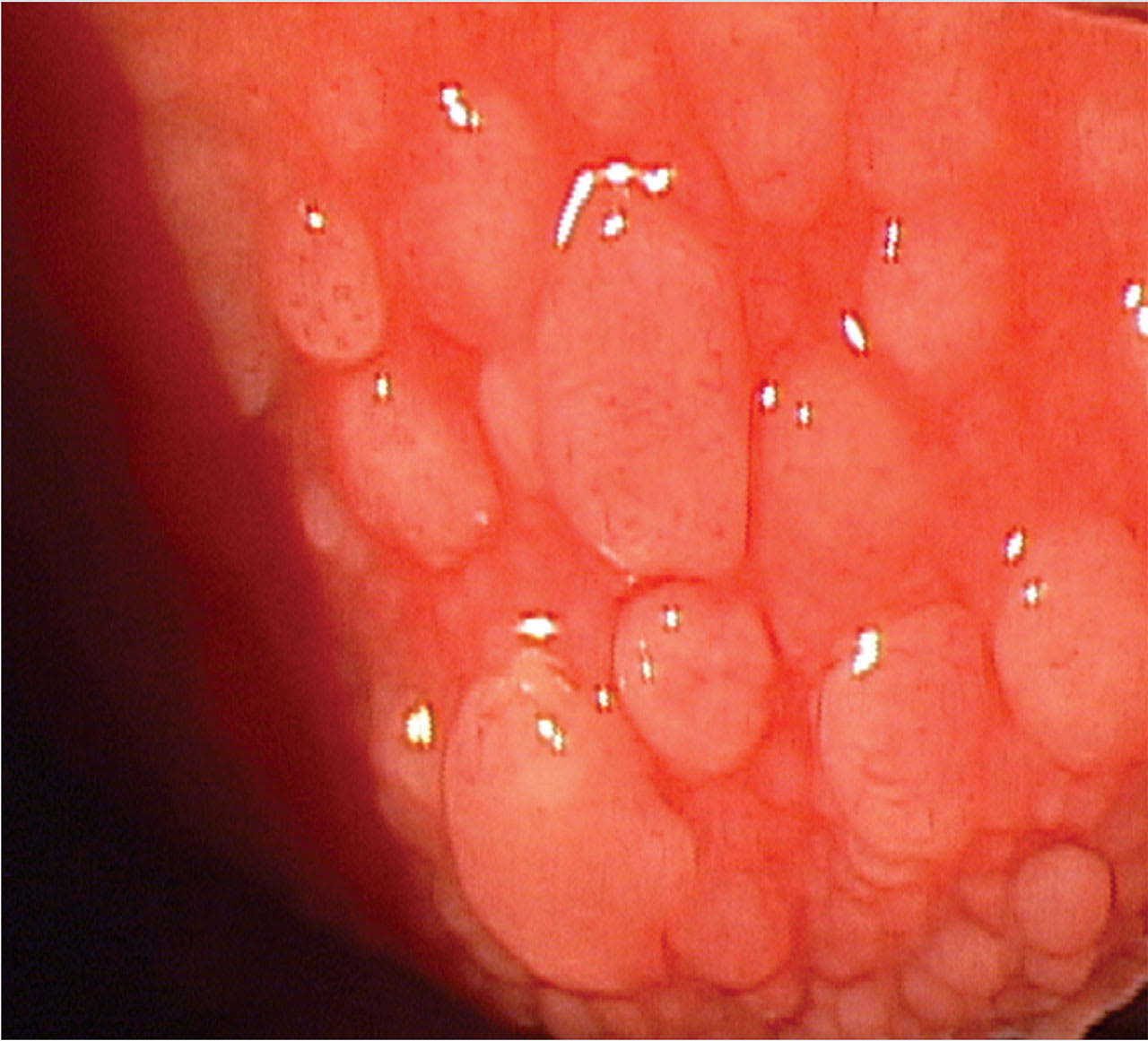

2. Look at the lids/ocular surface. A slit lamp examination of the lids can also aid in arriving at an accurate diagnosis. In ocular allergy, the lid will generally be swollen with papillae and have a velvety appearance. Additionally, the cornea may be involved superiorly. In advanced vernal keratoconjunctivitis, the superior cornea may be significantly affected due to inflammatory cell infiltration, mechanical damage from large papillae on the upper eyelid, and the release of toxic inflammatory mediators, leading to neovascularization, formation of shield ulcers, and scarring.1

Viral or bacterial conjunctivitis can also result in a ptotic lid position, due to severe conjunctival papillae.

Scaling of the lids, meibomian gland dysfunction, and collarettes from Demodex would indicate blepharitis. Also, the cornea generally shows inferior staining in this condition.

Something else to consider: Discharge that is purulent or mucopurulent is a sign of infection, while a watery discharge could be viral, but is more likely a sign of allergy.2 DED tends to result in thin, watery tears, as the eye tries to find homeostasis from the tear film instability and hyperosmolarity.2

3. Assess the tear film. Patients with pre-existing DED often have an inadequate tear film. In aqueous-deficient dry eye, tear hyperosmolarity is caused by reduced lacrimal secretion, limiting aqueous production.3 In evaporative dry eye, the hyperosmolarity is a consequence of excessive evaporation due to an inadequate lipid layer.3

Tear hyperosmolarity in either case gives rise to morphological changes within the cornea and conjunctiva that ultimately contribute to tear film instability.3

Something to consider: Both tear instability and reduced tear volume prevent proper elimination of allergens through the punctum, which further aggravates the ocular surface and exacerbates inflammation in patients who have comorbid allergic conjunctivitis.

To assess the tear film, the optometrist can evaluate corneal staining, tear breakup time, tear meniscus height, tear volume with a Schirmer test, lipid layer thickness with an interferometry device, or measure tear volume with a tear osmolarity device.

Studies suggest that a thickened lipid layer, reduced goblet cell density, and increased production of inflammatory cytokines are found in allergic conjunctivitis patients.4 These qualities affect the ocular “ecosystem” by reducing tear film stability and promoting shortened tear break-up time, as well as increasing inflammatory stress to the ocular surface. Frequent eye rubbing, which is associated with allergic conjunctivitis, further adds to this issue by releasing histamines and other inflammatory mediators that disrupt and damage the ocular surface. These changes often lead to worsening DED when allergy co-exists.

4. Acquire allergen test results. This can be achieved via referral to an allergist or, if scope of practice allows, in-office skin prick allergy tests.

Current Ocular Allergy Interventions

The following are available for ocular allergy:

1. Avoiding/reducing allergen exposure. As an example, if the patient is allergic to dog dander, it makes sense for the OD to educate the patient to steer clear of dogs. When it comes to reducing the allergen exposure, the optometrist can educate the patient to, for example, wash their hair before bedtime to avoid excessive amounts of allergen transfer to the pillowcase.

2. Using chilled, preservative-free tears. These work to clear the allergens from the eye, reduce the hyperosmolarity of the tears, and constrict the conjunctival blood vessels, to provide comfort.

3. Using cool compresses. These decrease allergen-caused inflammation and alleviate itching.

4. Using an oral antihistamine. These provide relief of systemic symptoms for allergy sufferers, though they may also decrease tear production, predisposing a patient to dry eye symptoms.5 However, the allergic response and subsequent inflammation without these oral medications will also result in decreased tear production. Therefore, these medications may be necessary to reduce overall inflammation to allow for a natural increase in tear production.

5. Using a topical mast cell stabilizer. These are ideal during peak seasons when symptoms flare up. The reason: Mast cell stabilizers aim to preclude histamine release. Histamine release causes ocular allergy symptoms.

6. Using a topical antihistamine. These are ideal for relieving ocular itch, as they work quickly to reduce histamine release. A caveat: They are not ideal as a long-term treatment. This is because they don’t stabilize the mast cells and will need to be used continually.

7. Using a topical mast cell stabilizer/antihistamine combination drop. This works to decrease the clinical signs and symptoms of ocular allergy, while precluding forthcoming reactions to the one or more offending allergens. The latter occurs thanks to the mast cell stabilizer. Of note: Ocular allergy eye drops may be more effective for allergic rhinitis than oral agents (that may exacerbate dryness symptoms) since they arrive at the eye fast and efficiently.

8. Using a mild topical steroid. When conservative treatment isn’t enough to aid in patient symptoms, a mild topical steroid could be considered. However, the optometrist should council patients regarding chronic use and the importance of being checked for intraocular pressure increases, if used for more than 2 weeks.

Future directions for combined therapies when both conditions co-exist include anti-leukotriene receptor antagonist and pathway blockers, anti-platelet activating factor receptor antagonists, anti-IgE therapies with regulation of adhesion molecules and chemokines, cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.1%, and a dexamethasone ophthalmic insert. In the meantime, we have an arsenal of options to help manage these conditions.

Getting the Answer

This discussion highlights the importance of a detailed case history (including family history and drops used in the past) and thorough clinical examination to determine whether DED or ocular allergy, or both, are most likely responsible for patient symptoms. Once a definitive diagnosis is made, treatment can be tailored to the ocular allergy and/or DED. Addressing each condition individually and treating them to their fullest extent (including lifestyle changes), helps the patient achieve the relief they need to improve quality of life. OM

References

- Bielory L, Goodman PE, Fisher EM. Allergic ocular disease. A review of pathophysiology and clinical presentations.Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2001;20(2):183-200. doi:10.1385/CRIAI:20:2:183.

- Baab S, Le PH, Gurnani B, Kinzer EE. Allergic Conjunctivitis. In:StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; January 26, 2024.

- Wolffsohn JS, Benítez-Del-Castillo J, Loya-Garcia D, et al. TFOS DEWS III Diagnostic Methodology.Am J Ophthalmol. Published online May 30, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2025.05.033.

- Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report.Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276-283. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008.

- Akasaki Y, Inomata T, Sung J, et al. Prevalence of Comorbidity between Dry Eye and Allergic Conjunctivitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.J Clin Med. 2022;11(13):3643. Published 2022 Jun 23. doi:10.3390/jcm11133643.