I inherited a patient who was prescribed latanoprost in each eye q.h.s. He had LASIK approximately 15 years ago and was being treated by a local ophthalmologist for glaucoma. Because of his LASIK history, I made sure to have a corneal map/pachymetry performed by my staff at his first visit.

While there is not a good and accurate formula for adjusting intraocular pressure (IOP) based on pachymetry—especially post refractive surgery due to the altered hysteresis of the post-op cornea—I needed to know just how thin his cornea was and whether to mentally factor that in when considering the IOP portion of the clinical data. His central corneas were 474 µm and 476 µm thick. I then took this into account when determining if I was comfortable with the treated IOP. While an elevated IOP was detected at one of the patient’s visits, he showed what appeared to be an acceptable IOP at most visits (see Figure 1). Overall, though, I was comfortable with the patient’s IOP on just latanoprost.

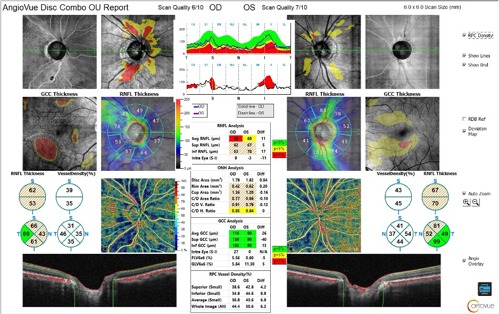

At his initial exam, optical coherence tomography angiography (OCT-A; Optovue Solix, Visionix) of the optic nerve and macula revealed focal inferior ganglion cell complex (GCC) and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinning in the right eye, and less focal GCC thinning in the left eye along with less focal RNFL thinning (see Figure 2). There was also considerable epiretinal membrane in the right eye and moderate peripapillary perfusion loss, which corresponded to the RNFL thinning.

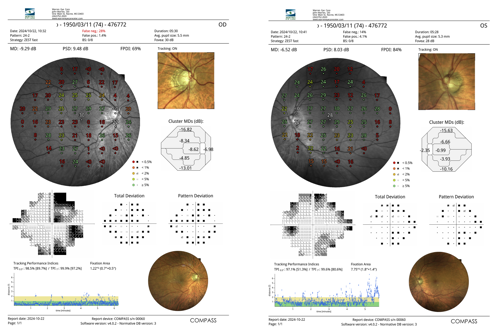

The patient was brought back to the office for threshold visual field testing, which showed corresponding defects (see Figure 3). In this case, the VF defects, structural damage, and microvascular loss all agree and fit together nicely. I love it when a case comes together! However, over the last half decade using OCT-A to follow my patients, significant perfusion dropout like this raises some “back of the mind” concern about progression, since these patients seem to me to progress more quickly. Further study in this area is certainly needed to allow for a better understanding of the order of development, perfusion loss driving structural loss, or the opposite. I am personally convinced that many of my “low-tension glaucoma” patients are really patients with poor peripapillary blood flow who have a vascular issue, not as a result of increased IOP. Anyone who has been caring for glaucoma patients for more than 10 years knows that while we have a good understanding of glaucoma, there is still much that we do not know.

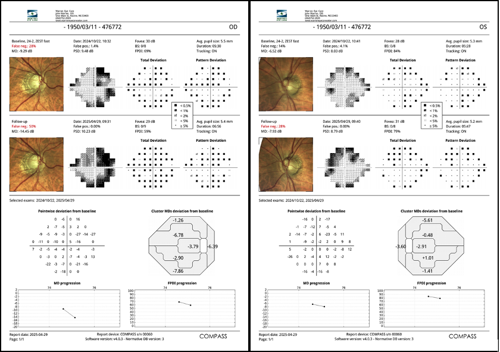

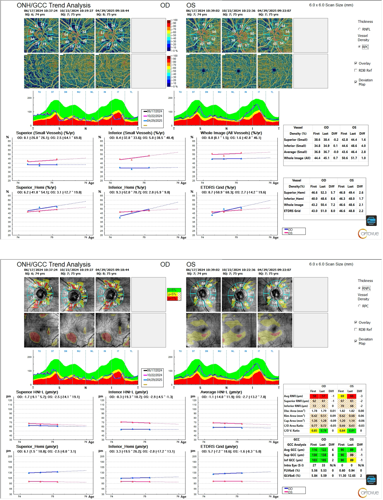

We have now performed multiple OCT-A studies (see Figure 5) as well as visual field studies (see Figure 4) on this patient, which show stable structure in each eye along with stable perfusion loss. As you can see, the visual fields have also remained stable (see Figure 4). I now have this patient on a follow-up schedule of a visual field test and OCT-A every 6 months.

Because of the perfusion loss and the presence of visual field defects, I am moderately concerned about this patient’s long-term prognosis. I will be keeping close tabs on both the OCT-A and visual fields each time I see this patient.